There may be no more important capability a person can have in the 21st century than knowing how to innovate. Not just professional innovators, but every one of us. Personal innovativeness is not a single attribute, but rather a whole constellation of behaviors that in combination fulfill all of the diverse capabilities that innovation requires. That includes being imaginative, exploratory, observant, reflective and empathic. It’s being adaptive, resourceful, creative, disciplined, inventive and insightful. It’s acting with courage, perseverance and integrity, while maintaining a sense of curiosity and humility. It’s being collaborative and coachable and knowing how to bring out these attributes in others.

That’s an impressive list of life skills that serve us well whether we’re actively striving to innovate or just navigate this rapidly changing world. It’s hard to imagine any context or role where they would not be helpful. It’s also a lot just to keep track of, much less measure or strive to improve. Thankfully, there’s an easier way to cultivate these important personal assets.

In my last post, I discussed how important innovativeness is to achieving innovation and the tremendous value it creates. Now it’s time for me to explain just what I mean by innovativeness, and that requires explaining a little innovation theory.

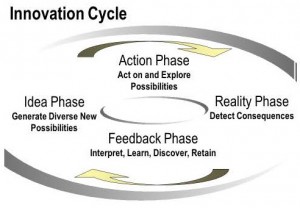

In a recent article in the International Journal of Innovation Science, Valuable Novelty: A Proposed General Theory of Innovation and Innovativeness, I describe a pattern that is common to all types of innovation, in any context. That includes nature, science, technology, society, business, government, anywhere innovation may occur. This pattern is called the Innovation Cycle, and it has four primary components.

- A source of new possibilities that I call the Idea Phase. In nature this is a genetic mutation, in science a hypothesis, in technology an invention, and in business an idea for a new product, service, process, business model, etc.

- An Action Phase in which new possibilities are explored and tested. In nature this is a mutation made manifest in an organism, in science it’s the experiment, in business it’s the process used to explore and develop ideas in order to determine whether they work or not.

- A Reality Phase—or the inevitable “reality check,” where an attempted innovation has some impact and creates value, or fails to. In nature this is survival, in science it is research data and findings, in technology it’s proof of concept, in business it’s customer acceptance or rejection.

- A Feedback Phase where we gain insights, make discoveries and retain we have learned. In nature, this is reproduction that passes along the genetic change, in science it’s the interpretation of the findings and making new discoveries, in technology this is adoption, in business it can be anything from gaining new customer insights to achieving traction in the marketplace and generating sustained revenues. This is where what succeeds is retained and used to inform the generation of more new ideas, and back to 1).

The Innovation Cycle is an iterative process of generating possibilities, testing them to see whether they create value, making discoveries when something is successful and gaining new insights even when it fails. It is an open feedback loop that constantly adapts and evolves, and it appears to describe the essential characteristics of every known approach to innovation.

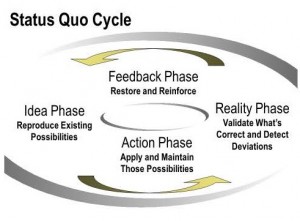

There is another equally prevalent pattern that I call the Status Quo Cycle. It too is found all around us and it has the same four phases, but they function in an entirely different way. Rather than adapting and evolving, the Status Quo Cycle maintains and preserves.

- In the Idea Phase, the Status Quo Cycle draws on existing mechanisms, processes, knowledge and expertise.

- In the Action Phase, those established processes are applied and maintained.

- In the Reality Phase, any deviations are noted, so they can be corrected.

- In the Feedback Phase, needed adjustments are made to fix any problems and maintain the original approach, to keep things moving along within a target range.

The Status Quo Cycle is a closed feedback loop that “detects and corrects” just like a thermostat maintains the temperature in a room. Nature uses this mechanism to regulate everything from our blood chemistry to our body temperature, and therefore keep us alive. The same detect-and-correct pattern is widely used in technology. It’s how we kept the Mars Explorer on course and keep our car in our lane as we head down the highway (and when Google is driving a car down the highway). In business it’s all the many business processes that need to be sustained. Things like budgets & accounting, sales & marketing, revenues & profits—all the things that keep a business alive and healthy.

Both patterns are useful and important, but one drives innovation while the other resists it. This is one reason I argue that treating innovation as just another business process is misguided. It is fundamentally different from the detect-and-correct approach so common in business. Assuming they are somehow the same creates confusion and dysfunction.

Most business managers spend the vast majority of their time navigating the Status Quo Cycle, as they probably should. It’s what keeps the business running. But unfortunately this pattern is so ingrained in the way we think about business that it leads to decisions that strongly resist innovation. Those decisions are often made with the best of intentions, because the folks making them simply do not see these patterns, much less recognize their impact. Those who are innovative still care about maintaining established processes, but they’re always striving to improve them.

These two patterns are near perfect mirror images of each other. So, by posing a series of choices about someone’s values, beliefs and behaviors, it’s possible to determine which pattern they tend to favor and in what ways. For example, is someone more comfortable drawing on their knowledge or applying their imagination? Would they prefer to confirm their beliefs or gain new insights? Following either cycle is perfectly rational. Yet nearly everyone prefers one or the other, and by varying degrees that can be measured along an Innovativeness Index. The lower someone falls along this 0-100 point scale the more they tend to favor the Status Quo Cycle; the higher they score the more they favor the Innovation Cycle—and the greater their innovativeness.

The research is clear that these two cycles are not equivalent in value creation—not even close. At the low end of the scale, value creation is very modest, while at the high end it’s quite dramatic, and there does not appear to be any upper limit. There is no point of diminishing returns. Value creation just keeps accelerating the higher you go up the scale. Simply put: the more someone favors the Innovation Cycle the more value they are likely to create, and the high scorers are not creative eccentrics. They are accomplished innovators and entrepreneurs who know how to make things happen, and are among the most successful at doing that.

We are all capable of being innovative, but some of us have a mindset that enables us to tap into that capability in ways that others cannot. Yet we all have the power to make different choices—to change our mindset in ways that enhance our innovativeness—our ability to create value.

When we focus on the pattern of the Innovation Cycle, we free ourselves. Instead of trying to somehow manage that long list of advantageous personal attributes I mentioned above, we can focus on the task at hand. Of course, being an effective innovator involves more than just changing our mind. But it’s a good place to start because so many of our decisions and actions are driven by our mindset, often in ways we don’t realize.

The Innovation Cycle is the universe’s killer app. We are not using it nearly as much as we could be. In a world with so many problems to solve, it’s time to put more emphasis on developing our innovation competence—our innovativeness. In my next post, I will explore why mindset is such an important consideration when it comes to fostering innovation.

Leave A Comment