The Foundation of Innovator Mindset

Innovator Mindset® takes a thoughtful research-based approach, building on scientific work in both mindset and innovation. This methodology provides a theoretical and practical umbrella that encompasses all of the diverse practices and perspectives that have come to represent innovation in so many different settings.

To help you understand this methodology, the following Q & A explains key concepts and how they’re applied.

An Innovator mindset—or innovative mindset, or innovation mindset—is generally taken to mean someone who thinks and behaves like an innovator. Someone who is predisposed to be innovative. It includes being 1) imaginative and creative, 2) brave and willing to take risks, 3) someone who’s curious and makes astute observations about the problems and challenges they face, and 4) open to understanding the world in new ways.

In other words, an innovator mindset is not a single attribute, but rather the whole constellation of capabilities that innovation requires. It’s a mindset that generates a wide range of valuable behaviors. That Includes welcoming new ideas and possibilities. It means being willing to explore and experiment with those possibilities. It requires being prepared to discover that you’re wrong and admit failure, so you can adjust and pursue alternatives. It includes being open, flexible and collaborative. Welcoming other’s ideas and perspectives.

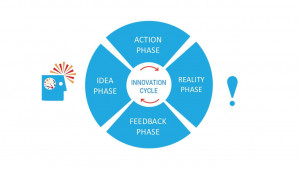

- A key insight behind Innovator Mindset® is that these behaviors are not just some checklist. They combine to form a larger pattern or Innovation Cycle. Their strength comes from that dynamic pattern that moves from observation to interpretation to imagination to action and back to observation. Each step in that cycle—and the behaviors it implies—is crucial to being an effective innovator.

There are many definitions of mindset. An Australian researcher recently cataloged more than a hundred, spanning research and theory in many disciplines. Various possible synonyms include attitude, paradigm, world view and mental models. All too often, the term mindset is used without any clear definition—even in the mind of the person using it.

Carol Dweck, who’s done widely regarded research into growth and fixed mindsets, defined mindset as implicit theories. They’re a person’s theories about how the world works, but at a level that’s frequently subconscious and unexamined. Those theories are implied by a person’s values, beliefs and behaviors.

- Innovator Mindset® adopts Dweck’s theoretical framework for mindset and applies it to innovation. This approach describes mindset as the often-subconscious assumptions and beliefs we all have. The things we just assume to be true without thinking about it. These ingrained mental habits shape how we experience the world around us and respond to it. While these habits impact a person’s ability to innovate, they extend far beyond that, shaping all aspects of our lives. Yet, we’re frequently unaware that we’re making those assumptions, much less recognize their effect on us.

Changing your mindset is more complex—and powerful—than simply changing how you think. Your mindset is something your brain does automatically outside conscious awareness. It’s all the assumptions, beliefs, expectations and biases you already have. That means when you’re making a decision, your mindset has already kicked in, influencing that decision in ways that are often invisible to you. Yes, you can decide to override your mindset, but that’s difficult when you’re not aware of its effect on you—or even that it’s there—which is frequently the case.

Gaining control of your mindset requires first identifying those hidden assumptions. Then, you need to consciously examine them and decide which ones you want to change. It’s getting out in front of your mindset by developing new mental habits. So when your mindset kicks in, it does that in ways you’ve decided are beneficial. That way you gain control over your mindset, rather than allowing it to control you.

Innovation proponents have offered many different definitions over the years. Some require that it somehow produces a profit. Others, that it’s something new to the world. One of the most universal definitions—the one used here—is simply valuable novelty. If something is new and it provides some sort of value, it counts as an innovation. If it doesn’t do those two things, it’s not. This definition is deliberately broad, to capture the many ways innovation can occur. Valuable novelty is not intended to replace those many other definitions, but instead to encompass them.

An innovation need not be new to the world, just new in some context. Borrowing ideas from other disciplines is a common innovation practice. Henry Ford was inspired to invent the manufacturing assembly line after visiting a meat packing plant that used what might be called a disassembly line.

The value created may be profits, but it can also take many other forms. In nature, it may be an adaptation that enhances a specie’s survival. It can be a useful new product or service or solution to a problem. Or, it might be a scientific discovery, some new technology, a new law, or a beneficial social change.

If we take the definition of innovation to be valuable novelty, innovativeness is simply the ability to produce valuable novelty. This means innovativeness is not just a human characteristic. It includes human innovators—the inventors, entrepreneurs, scientists, creatives and reformers that drive innovation. And it includes nature, which has been innovating for eons. It arguably includes artificial intelligence, at least potentially.

A research and development team possesses innovativeness, as does an innovative business startup, and companies or teams that successfully evolve their products, processes and business models.

Innovativeness is not the same as creativity. It includes being creative, along with other attributes not typically associated with creativity per se. Things like making astute observations, being willing to take risks, and reflecting on your own mental processes. Psychologists call that metacognition and it gives you the ability to innovate yourself. That’s innovativeness too, and it’s the focus of Innovator Mindset®.

An innovator mindset is a set of mental habits that embrace rather than resist innovation. Developing those habits requires two things: 1) understanding your current mindset, where you are now, and 2) understanding what mindset is going to be most helpful, where you want to go.

That first step is deeply personal. No two people have exactly the same mindset. We each have our own strengths and gaps. The second step is universal. Everyone needs to be headed for the same destination, maximizing innovativeness, and that’s well-researched and understood.

- Innovator Mindset® uses a unique rigorously validated personal self-assessment to measure a person’s current mindset across twelve dimensions. We can all use some help surfacing our hidden assumptions. You then receive a 21-page report detailing your mindset and providing guidance on how to make shifts that will enhance your innovativeness.

- Innovator Mindset® uses a variety of interventions—keynotes, workshops, elearning, etc.—to explain the mindset of highly effective innovators. Not all interventions include a personal assessment, but participants still gain increased self-awareness and learn how to become more effective innovators.

The Innovation Cycle describes the core dynamic of all types of innovation. Whether that’s in nature, science, technology, new product development, social change, or anywhere innovation occurs. Yes, there are important distinctions between different types of innovation and innovation processes, but they all follow this fundamental pattern. Innovation is innovation is innovation.

All innovation processes, including natural selection, the scientific method, design thinking, lean startup, creative problem solving, TRIZ and others, follow this cycle. (Although some do it better than others.) This cycle can be broken down into four steps or phases that follow a specific sequence.

Idea Phase: This is the generation of new possibilities. It can be a mutation in nature, an idea for a new product or venture, a scientific hypothesis, proposed legislation, or any new idea that may occur through ideation, or simply having an “Aha!” The outcome of this phase is ideas.

Idea Phase: This is the generation of new possibilities. It can be a mutation in nature, an idea for a new product or venture, a scientific hypothesis, proposed legislation, or any new idea that may occur through ideation, or simply having an “Aha!” The outcome of this phase is ideas.

Action Phase: This is pursuing some possibility. That may be an entrepreneur putting a team together to launch a venture. It may be a scientist conducting an experiment, an inventor building a prototype or the effect of a mutation on a living organism. The outcome of this phase is some impact.

Reality Phase: This is the environment or context that provides feedback and determines whether a possibility is viable. The proverbial reality check. This may be customer response, technical performance, or whether some living organism survives. The outcome of this phase is information. That may be scientific data, sales figures, or personal observations.

Feedback Phase: This is what happens due to that reality check and how we come to understand it. This may be research findings, natural reproduction, or interpreting data on customer preferences or sales. It’s where you make sense of what’s happening by reflecting on the information gathered in the Reality Phase. The outcome of this phase is insights, which then inform the generation of more new ideas and so on.

The Innovation Cycle is an iterative process that continually progresses through these four phases, from Ideas to Impact to Information to Insights to more Ideas and so forth. Because this is a recurring cycle, any of these steps can serve as a starting point, depending on the context and objectives.

Research has clearly demonstrated that those who are most innovative have a strong preference for following the Innovation Cycle. It describes their mindset.

- Recognizing the Innovation Cycle and its universal nature was the key insight that inspired Dennis Stauffer to undertake this work, including founding Innovator Mindset®. The Innovator Mindset® assessment, elearning and other materials are all grounded in this concept.

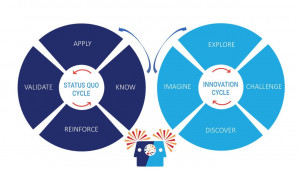

Of course, not everyone is an innovator. Some actively resist it, and these are not random behaviors. They reflect a particular mindset. Shorthand for this is “detect & correct”. Whenever you detect something that isn’t what you expect or think should be, you feel an urge to correct it.

This dynamic is all around us. Detect & correct is how we raise and educate our children; how we expect people to do their jobs; and how you keep your car in your lane on the highway. It’s embedded in all sorts of technologies, from smart phones to satellites, and it can be quite useful. Unfortunately, when it becomes someone’s dominant mindset, it shuts down the ability to innovate. This is because it prompts you to keep circling back to the same assumptions and beliefs. It makes you resist the novelty and variation that leads to innovation.

A detect & correct mindset relies on prior knowledge rather than imagination. It then applies that knowledge instead of exploring or testing it. It then looks for validation that it’s right. When that happens, it reinforces that prior knowledge. So a person keeps circling back to wherever they started. It shouldn’t be hard to see how that interferes with the ability to innovate.

Just as an Innovator Mindset follows the Innovation Cycle, an innovation-resistant mindset has its own dynamic pattern—a Status Quo Cycle. The Status Quo Cycle mirrors the Innovation Cycle, phase by phase.

Just as an Innovator Mindset follows the Innovation Cycle, an innovation-resistant mindset has its own dynamic pattern—a Status Quo Cycle. The Status Quo Cycle mirrors the Innovation Cycle, phase by phase.

This creates a series of choices or preferences. Between:

- Relying on your Knowledge or engaging your Imagination

- Applying your knowledge or Exploring new possibilities

- Looking for Validation that you’re right or Challenging yourself to see things accurately—even when it tells you you’re wrong.

- Hoping to Reinforce your existing knowledge and beliefs or Discover something new.

An Innovator Mindset fosters curiosity, humility and taking thoughtful risks. A Status Quo Mindset breeds defensiveness, arrogance and dogmatic thinking.

This does not mean your knowledge and expertise is bad. It can be quite valuable. Detect & correct can be useful. Some things need to be corrected. It’s the larger dynamic described by the Status Quo Cycle that’s problematic. It’s having that dominant mindset that gets us into trouble.

Few of us have a mindset that exclusively follows one cycle or the other. Most of us blend the two in ways that fail to fully leverage the benefits of either pattern. But nearly everyone favors one mindset or the other. Maybe by a little. Maybe quite strongly. The ability to recognize these patterns, in ourselves and others, is a powerful cognitive compass that can guide you to strengthening your innovativeness.

The Innovativeness Index is a measure of personal innovativeness. It’s a hundred-point scale that reflects how innovation-friendly or innovation-resistant someone’s mindset is. The higher the score, the more innovation-friendly. The lower the score, the more innovation-resistant.

This index is composed of twelve dimensions, each measured and validated independently. These dimensions include a scale for a person’s beliefs (cognitive profile), values (values profile), and behaviors (behavior profile). These three profiles are measured within each of the four phases of the Innovation Cycle.

|

Twelve Dimensions of the Innovativeness Index |

|||

|

|

Cognitive Profile | Values Profile | Behavior Profile |

|

Idea Phase |

? | ? |

? |

|

Action Phase |

? | ? |

? |

|

Reality Phase |

? | ? |

? |

|

Feedback Phase |

? |

? |

? |

These scores reveal how innovative someone is, in what ways, and how strongly, within each dimension. This provides a richly detailed Snapshot report of where someone is now, and what steps they can take to increase their Innovativeness Index. It’s called a “snapshot” because it captures a person’s mindset at a moment in time. That can change—sometimes dramatically—because unlike personality, mindset is developable. Anyone can make crucial shifts in mindset that will enhance their innovativeness.

- The Innovativeness Index and Snapshot report are produced by the Innovator Mindset® assessment.